All Americans are lucky to live in a country brimming with public resources that everyone can share.

Many are provided by government and funded with our tax dollars, such as the highways that crisscross the country, the 84 million acres of national parks and the roughly 100,000 public schools that give all children access to education.

Others come from nature, like mountains, lakes and rivers, which also depend on a reliable government and meaningful regulations to preserve and protect them.

While the collective value of these “public goods” is probably incalculable, the economic impact of schools, clean air and vast highways has been significant. In fact, I would argue that public goods are what have made America great.

Unfortunately, our stock of public goods has been declining for half a century, particularly those that require the government’s purse strings. President Trump’s proposed budget would make things even worse by cutting, among many other things, funding for national parks, the cleanup of the Great Lakes and efforts to minimize climate change.

So if Trump is serious about making America as great as it can be, investing in our public goods – as well as those equally vital ones we share with other nations – would be a good place to start.

Nonexcludable and nonrivalrous

The formal definition of a public good is that it’s something that is nonexcludable and nonrivalrous. That’s a fancy way of saying that everyone can take advantage of it and that one person’s use doesn’t reduce its availability to others.

Setting aside for a moment natural public goods, the ones provided by the government have been on the decline. U.S. public capital investment, net of depreciation, fell to just 0.4 percent of GDP in 2014 from 1.7 percent in 2007 and about 3 percent in the 1960s.

A particularly critical subset of this, research and development spending, has been the bedrock of innovation and growth in our economy. It has dropped from a high of 2.1 percent of GDP in 1964 (during the Cold War and space race) to less than 0.8 percent in recent years.

A history of public goods investment

This erosion has persisted through both Republican and Democratic administrations. But it was not always thus, as the bipartisan history of our biggest undertakings attests.

The transcontinental railroads, though privately built in the mid-1800s, were heavily subsidized by generous grants of federal land under several presidents and was vital to 19th-century economic growth. As one illustration, before the railroads, it took almost six months and US$1,000 to travel from New York to California. Afterward, it cost just a week and $150.

Similar gains came after 20th-century presidents invested heavily in public works. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, established the National Park Service in 1916, a few years after Republican Theodore Roosevelt greatly expanded their number. U.S. parks are now responsible for more than $200 billion a year in economic activity.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the quintessential Democrat, built schools, post offices, libraries and many other public buildings in the 1930s. And Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower created the interstate highway system that bears his name in what was the biggest public works project in history. In 1996, an estimate put its total economic benefit at well over $2 trillion, or about six times the original cost.

Why we stopped investing

But since the 1960s, the bipartisan consensus in support of public goods has broken down, as the right’s pressure to cut taxes and the left’s efforts to expand entitlements squeezed the discretionary part of the budget – from which support for public goods comes.

Both parties have moved further from the center, where bipartisanship resides and makes large public works projects easier to build and fund. Meanwhile, a focus on reducing spending has meant that many once public goods have been fully or partially privatized.

Finally, research has shown that ethnic and racial heterogeneity reduces support for public goods such as trash collection and public education because the dominant groups don’t like the idea of sharing these resources with the newcomers. In other words, racism seems to play a role.

Sharing internationally

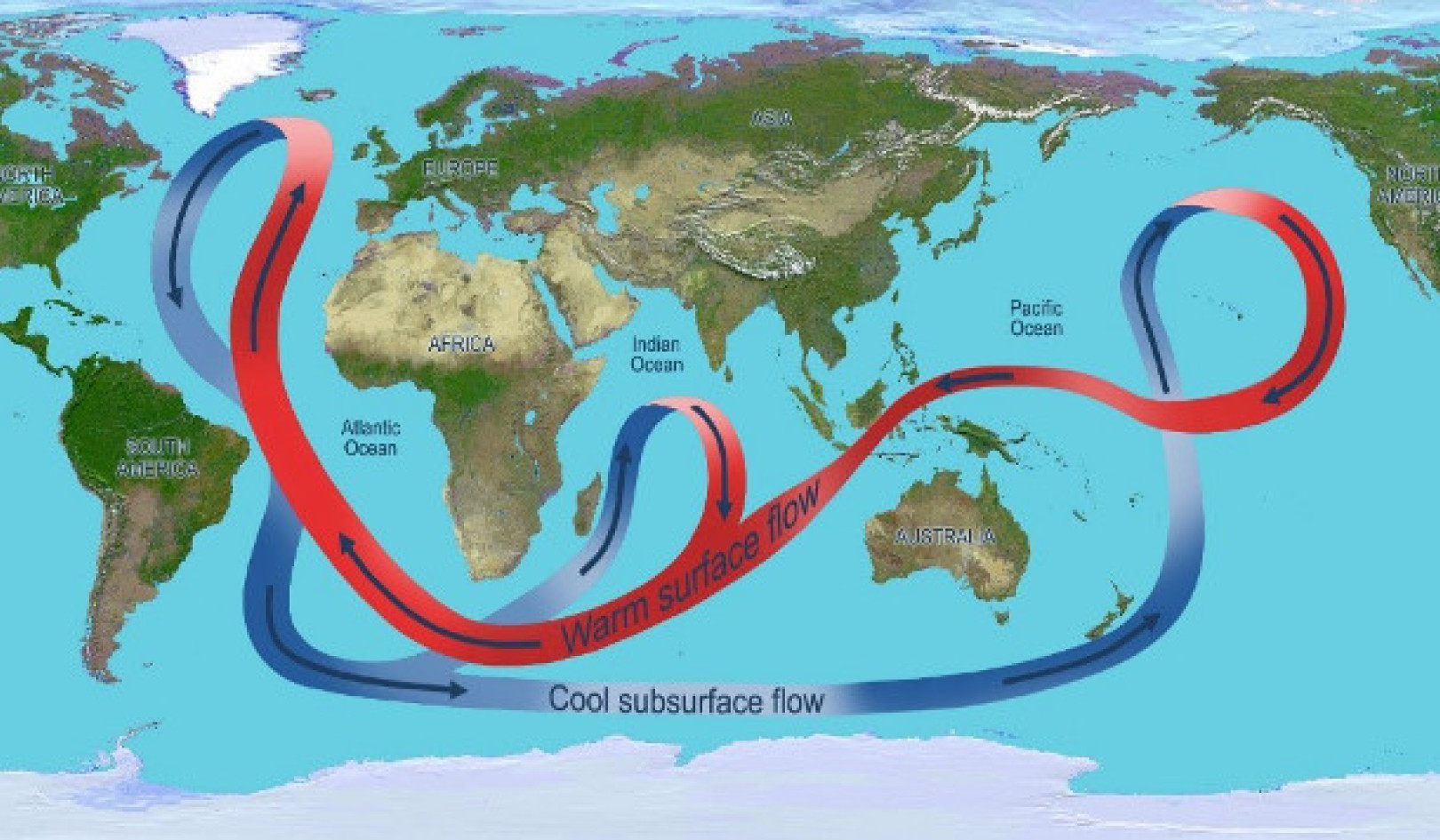

A bright spot for public goods has been those shared across borders, which have proliferated since World War II.

The U.S. took the lead in establishing some of the key international institutions – such as the United Nations and the World Bank – that provide public goods to the world. Healthy oceans, a stable climate and cross-border money transfers require international coordination for their protection.

Perhaps the most critical global public good is peace. While there have been many regional wars, a third world conflict has been avoided, in no small measure because, in the aftermath of World War II, the United States undertook to stabilize key regions of the world through military expenditures, strategic alliances like NATO, and economic assistance. Although increasingly frayed and fragile, these arrangements, dubbed the Pax Americana, have so far held.

The broadest, if not the sturdiest, steward of public goods has been the United Nations and its associated agencies. Freedom of navigation, for example, is protected by the U.N.‘s Law of the Sea. The United States also led in the creation of the World Trade Organization, which sets the rules for international trade and the settlement of disputes.

Turning our backs?

Now, not only does the Trump administration wish to significantly slash spending on already deteriorating U.S. public goods, it wants to cut funding for global institutions such as the U.N. as well. One exception is his plan to invest in infrastructure, but little of the $1 trillion total would actually come from the federal government.

This is a supreme irony given the benefits our country derives from public goods, from the parks and highways to the global institutions that support trade and other international public goods.

Imagine for a second what life would be like if you didn’t have the public park down the street where you can play freely with your children. Or if the rivers and lakes you swim in returned to the more polluted levels common in the past. Or if our public schools were public no longer.

Put simply, investing in public goods has served America well through the years. It would be a huge mistake to turn our backs on it.

About The Author

Marina v. N. Whitman, Professor of Business Administration and Public Policy, University of Michigan

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon