It’s difficult not to position the 60s in stark contrast to our modern age: it was a time of great upheaval, yes, but also a time of great optimism in which countless social freedoms were fought for and won. Today, it feels as though some of those freedoms might increasingly come under question, at least in the US context. And in Britain, the recent furore over Brexit could not be more different to feelings about Europe in the early 70s as Britain prepared to enter the Common Market, a move which promised to usher in a new age of economic prosperity and international cooperation.

But while the social and cultural significance of the 60s can’t be denied, our collective view has become sophisticated enough to recognise that media representations of the 60s and actual memories of the decade-as-lived can often be two very different things. Everyone knows that this was an era of great leaps in art, creativity and popular music, but try telling that to someone who lived on the edges of Salford in 1966. There were strong undercurrents of post-war traditionalism running parallel to all this social and cultural change, particularly at the level of film and popular culture.

The 60s are the subject of the V&A’s current exhibition, You say you want a revolution?. Headsets fill with music and current events depending on where your interests (and your feet) take you, while gigantic screens play archive footage overhead.

Some have noted a lack of historical revisionism in the exhibition, but while it certainly doesn’t mount a huge challenge to the old prevailing narratives, neither is it an affair which unremittingly plays up the media-constructed-fantasy aspects of the decade.

It is interesting, for example, that one of the films chosen to represent the era in cinema is Desmond Davis’s (relatively unknown) Smashing Time (1967), a biting satire of the “swinging London” scene which is utterly scathing in its representation of posing youths, boutique culture and superficial media personalities in search of the next big craze. And Antonioni’s Blow Up, the film which led to changes in US censorship with the abandonment of the Hollywood Production Code in 1968, is given due prominence (and rightly so). But the exhibition curators don’t let us forget that those watching Blow Up on the big screen would have had to suffer through one of Rank’s dreary, old-fashioned and increasingly irrelevant Look at Life newsreel documentaries before the main feature.

In the midst of this sensory extravaganza sits disc jockey John Peel’s record collection, and viewers can even feel free to browse through some famous titles (Revolver) and some not-so-famous ones (Rolf Harris – Live!). The collection gives a brief nod to the fact that while the 60s was a revolutionary decade for popular music, Engelbert Humpedink’s Release Me still topped the charts for a whopping 56 weeks, keeping The Beatles’ Strawberry Fields Forever from the number one spot.

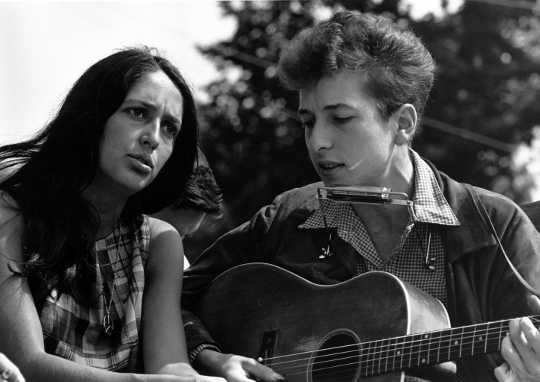

But it is revolution, not convention, which forms the exhibition’s focus: political protest, civil rights, the Black Power movement, the legalisation of homosexuality in Britain, second wave feminism and civil unrest in France in ’68.

Rose-tinted glasses

But there is something about the almost confrontational audio-visual nature of the exhibition which makes the past seem uncomfortably present; something that reminds us that, while the 60s was a was a time of important milestones in legislation and human rights, all is not exactly rosy from the vantage point of 2016.

Today, we live in an era of mass protest in which many of the legislative freedoms won in earlier decades are being threatened by a growing vein of conservatism in British and American life. Human rights are no longer a given, a woman’s right to control her body remains under question in the United States, and the current rhetoric around immigration on both sides of the Atlantic has conjured a wave of xenophobic feeling which seems to hearken back to a bygone era.

The fantasy of the “swinging 60s” has been recycled in modern life long after Mick Jagger’s epic drug-fuelled comedown in Nic Roeg’s Performance (1970). In the 1980s the Thatcher government pushed back against the indulgent excesses of the decade, attacking the permissiveness and moral decline which conservative cabinet minister Norman Tebbit argued had its roots in this watershed era of revolution.

From 1997, Tony Blair’s Labour government used the superficial, 60s-inspired success of “Cool Brittania” to represent Britain as a hub of creativity which was clearly visible on the international stage. And with Britpop the 60s lived again in the 90s, with many of the leading artists of the decade drawing their influences directly from artists like The Kinks and The Beatles. Those elements that had made the 60s responsible for societal ills ten years earlier had suddenly become saleable.

How and why do we continue to mythologise our national pasts? And to what ends? We see the 60s as an age of rebellion and great strides in fashion, film and modern art, yes; but also as an age of economic prosperity which stands as an unflattering mirror to our own. In modern Britain perhaps the most startling legacy of the era is one of inter-generational conflict between the “Baby Boomers”, many of whom who came of age in the 60s and enjoyed the spoils of cheap education and competitive mortgages, and today’s “Millenials” (or “Generation Rent”, as they’ve come to be known) who are facing an altogether bleaker future. But one doesn’t need to dig especially deep into this issue to find that the “Baby Boomer” stereotype also contains elements of myth.

If the social, cultural and economic legacies of the 1960s are still with us, it’s also clear that our fantasies of the era are still very much alive and swinging.

![]()

About The Author

Laura Mayne, Post-doctoral research associate in British Cinema History, University of York

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Related Books:

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon