After states suffer significant job losses, college attendance drops among the poorest students of the next generation, a new study suggests.

As a result, states marked by shuttered factories or dormant mines also show a widening gap in college attendance between rich and poor, the study’s authors write.

Yet simple economics aren’t the only factor at play, the authors write. Poor students in economically stricken states don’t avoid college simply because they can’t afford it. Instead, widespread job losses trigger adolescent emotional problems and poor academic performance, which, in turn, puts college out of reach, say the authors.

Credit: Duke University

Credit: Duke University

“Job loss has led to increased inequality in college-going not just because people lose income, but because they are stressed out,” says economist Elizabeth Ananat of Duke University, one of the paper’s lead authors. “Losing your job is traumatic, and even if a community is adding new jobs, jobs aren’t interchangeable.”

During the 2016 presidential race and since the November election, attention has focused on economically distressed regions where technology and globalization have obliterated jobs, and where worries run high about the next generation’s future and about growing inequality.

Some economists promote higher education as the natural remedy. According to this view, inequality will disappear as more young people choose college rather than “following their parents’ footsteps to the now-closed factory,” the authors write.

The new study tests that theory empirically, and finds it flawed.

“Our whole narrative as a country has been, creative destruction will push kids toward more profitable, growing industries,” Ananat says. “But if kids are stressed out and parents are stressed out, they may not be as nimble as we imagine people being.”

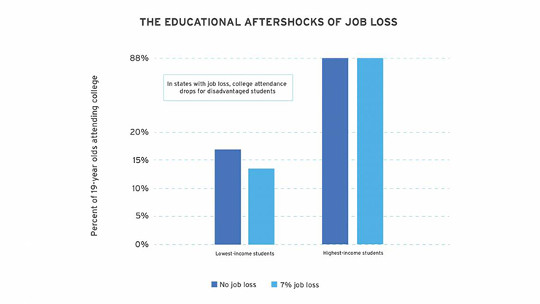

The authors compared job loss rates during middle and high school years with college attendance rates a few years later, at 19 years of age.

In states that suffered a 7 percent job loss, college attendance by the poorest youth subsequently dropped by 20 percent, even when financial aid increased. The pattern also persisted across a wide range of states, despite variations in public college tuition rates.

“Rather than clearing a path to new educational opportunities in deindustrializing areas, job destruction knocks many youth off the path to college,” the authors write.

The research points to a need for more rigorous job retraining programs, which could lessen the trauma of job loss for the whole community.

“Bringing back jobs that technology has replaced is not necessarily possible or desirable,” Ananat says. “Imagine if we had insisted on subsidizing the buggy-whip industry.”

“But that doesn’t mean we must abandon everyone to a terrifying future. Instead we could actually support people in getting new jobs.”

The new research also found that while job loss lowered college attendance among poor whites, the decline was even steeper for poor African Americans.

Furthermore, after widespread job losses, suicide, and suicide attempts among African-American youths rose by more than 2 percentage points.

“What happens with African Americans are the same things that happen to working class white people—just worse,” Ananat says.

“Yes, there have been losers from the changing economy.” Ananat says. “But white working class people and African-American working class people are in the same boat due to job destruction. Imagine the policies we could have if folks found common ground over that.”

The study appears in the journal Science. The Russell Sage Foundation supported the research.

Source: Duke University

Related Books:

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon