Image by Victoria from Pixabay

When I was around the age of five, my father left his job as a high school teacher and principal, a role that had nourished both his heart and mind. He relinquished this passion and, to support his growing family, became a dress manufacturer in the rough, tough, mafia-infested New York garment district.

This was a decision he later regretted, as it put our entire family in serious and prolonged jeopardy. But at the time all any of us kids knew was that rather than coming home in the late afternoon, he now came home between nine o’clock and eleven o’clock in the evening.

When I was about six, I tried to stay up as late as I could, and when the doorbell rang I would rush to the door and jump into his welcoming arms. That moment of joy filled me with the heartening feeling of protection and goodness. I recall the exact sensation of his rough whiskers brushing against my tender face. However, despite his late work hours, he reserved one day of the week exclusively for our family tobe together. Sunday was that special day.

Bicycle Built for Two -- and Five

When my father was in his early twenties (in 1936), he and a friend had taken the Île de France, a great ocean liner, from New York to Paris. There, they purchased a tandem bicycle and cycled together throughout France, and then on to Budapest, Hungary. After this odyssey, my father returned and brought the bicycle back home to the Bronx for our family to enjoy.

Our Sunday mornings usually began with bagels, cream cheese, lox, pickles, and smoked white fish from the local Jewish delicatessen. Then, with full tummies, we would run down to the basement where that hallowed, maroon tandem bike was stored.

My father had made some modifications to the old, well-seasoned bike. He had added extra seats: one just behind the front seat with an improvised handlebar, another jury-rigged on the rear baggage rack. Imagine this: Dad and Mom peddling the three of us brothers—me behind the front seat, Jon on the rear baggage rack seat, and baby Bob tucked snugly into the bike’s front basket.

People would file out of the neighborhood tenements and gawk at the sight of the five of us riding to Reservoir Oval Park. A lovely image. But mind you, like Reservoir Oval Park and so much of my early life, there was a dark and traumatic side to the bicycle’s origin story.

Shadows of the Holocaust

Upon arriving in Budapest in 1936, my father Morris found his way to the home of some of his relatives. There he witnessed an elderly Jewish shopkeeper dragged from his bakery at the end of the street and mercilessly beaten by a group of Crossed Arrow hooligans. Hungary’s right-wing Arrow Cross Party was nationalist to the extreme and modeled itself on Germany’s Nazi Party but, compared to the S.S. Storm Troopers, these thugs were even more venomous and vicious in their antisemitism.

My father readied himself to rush to the poor man’s aid. But thankfully, his relatives grabbed his arm and restrained him from dashing forth. In broken English, they commanded, “Stop! Don’t! You have to be crazy. They kill you both!”

Thus, in addition to the family bicycle, my father returned from his journey bringing home with him a horrific glimpse of the prelude to the Second World War. The specter of war had been looming on the horizon. Its menacing shadow was accompanied by the Nazi Holocaust, the slaughter of six million Jews alongside Catholics, Romani, homosexuals, the disabled, intellectuals, and other so-called “undesirables.”

The scourge of war and genocide was to shake the world to its very foundations—and my family’s world as well. As a child I didn’t understand why, aside from my father’s parents Dora “Baba Dosi” and Grandpa Max, I had no other living relatives on his side of the family. This seemed particularly unsettling because, on my mother’s side, I had not only my maternal grandparents but also aunts, uncles, cousins, and other relations. Apart from one cousin, all my father’s family in Europe had been murdered by the Nazis.

The Reunion: Survivor's Guilt

After the war, around 1952, the Red Cross had a program to unite refugees with possible family members living in the United States. Somehow they found a young man who had escaped from Auschwitz and had been surviving for two years in the forests, living like an animal on berries, roots, and leaves—one of the Forgotten Jews of the Forest or, as I put it, Forest Jews.

Along with my parents and grandparents, we went to meet Zelig, a distant cousin and my only paternal family member in Europe to survive the Holocaust. I remember being utterly haunted by the blue numbers tattooed on his forearm, and by his mysterious, barely comprehensible foreign accent.

Unbeknownst to me back then, a short time after Zelig’s unexpected visit, my paternal grandmother Doris “Baba Dosi” lifted her eighty-pound, frail, and cancer-ridden body to the window ledge of her apartment and jumped to a violent death six stories below. As I was eventually to realize, her suicide was a response to delayed survivor’s guilt, possibly brought on by the visit of Zelig, her one and only remaining distant relation in the whole world.

As I would also come to learn, these types of nightmarish traumas can be transmitted over multiple generations. Indeed these implicit memory engrams had a deep impact on my life, particularly on some of my behaviors, and my haunting and pervasive feelings of shame and guilt.

Memories: Lost and Found?

As I continued working with my clients’ implicit—or bodily and emotional—sensory memories, I was taken by surprise when a few of them reported the acrid smell of burning flesh. This was particularly unexpected since many of these people had been longtime vegetarians.

When I asked them to interview their parents regarding their family histories, a number reported that their parents or grandparents had been Holocaust victims or survivors. Was it possible these clients were somehow being impacted by a potent, racially specific, cross-generational transmission of their parents’ and grandparents’ trauma in the death camps? Given what was known about an individual’s memory at that time, this explanation seemed highly unlikely.

I remained puzzled by the specificity of how the smells from the death camps could possibly be passed on through generations to my clients. But then I recently came across some startling animal experiments carried out by Brian Dias at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. The researchers exposed a group of mice to the scent of cherry blossoms. I don’t know if it was pleasant to them in the way it is to humans, but certainly it wasn’t aversive. But then the experimenters paired the scent with an electric shock.

After a week or two of such pairings, the mice would shake, tremble, and defecate in acute fear when exposed only to the cherry blossom scent. That result is really no surprise, as it is a common Pavlovian conditioned reflex. However—and I am curious about what motivated these scientists—they bred these mice for five generations.

The denouement of these experiments is that when they exposed the great-great-great-grandchildren of the original mice pair to the cherry blossom scent, they shook, trembled, and defecated in fear just from the scent alone. These reactions were as strong as or even stronger than those of their great-great-great-grandparents who were initially exposed to the cherry blossoms paired with the unconditioned stimulus in the form of shocks.

The mice did not react with fear to a wide variety of other scents—only to the cherry blossom smell! A final, interesting outcome of this study was that the fear conditioning was transmitted more robustly when the male, or father, was the member of the original mating couple exposed to the conditioned fear reaction. This specificity is something that didn’t completely surprise me, as I had always felt that the Holocaust memories I myself encountered came primarily through my father.

Healing from Ancestral Trauma

The clinical question regarding this transmission was how to help my clients heal from deep-rooted ancestral traumatization that was passed on from generation to generation. How could I enable these individuals, and myself, to heal from such alarming memory imprints when the trauma had never personally happened to us? This inquiry was also highly relevant for people of color and First Nations people.

When I first spoke publicly about these generational transmissions in Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma, published in 1996, I was often criticized for making such preposterous suggestions. Today in 2023, however, an increasing number of research studies have confirmed such ancestral transmission and have even decoded the molecular basis for certain types of “epigenetic transmission,” using animal experiments.

Recently, I came across the writings of an “old friend” who, long before such research existed, and well before my speculations on generational transmission, postulated a similar perspective on ancestral influences. Carl G. Jung, in his book Psychological Types, wrote:

“all experiences are represented which have happened on this planet since primeval times. The more frequent and the more intense they were, the more clearly focused they become in the archetype.”

This might be one reason why wars are never truly over, and why there are no “wars to end all wars.”

Copyright 2024. All Rights Reserved.

Adapted with permission from the publisher,

Park Street Press, an imprint of Inner Traditions Intl.

Article Source

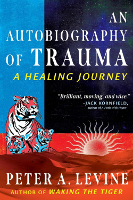

BOOK: An Autobiography of Trauma

An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing Journey

by Peter A. Levine.

In this intimate memoir, renowned developer of Somatic Experiencing, Peter A. Levine—the man who changed the way psychologists, doctors, and healers understand and treat the wounds of trauma and abuse—shares his personal journey to heal his own severe childhood trauma and offers profound insights into the evolution of his innovative healing method.

In this intimate memoir, renowned developer of Somatic Experiencing, Peter A. Levine—the man who changed the way psychologists, doctors, and healers understand and treat the wounds of trauma and abuse—shares his personal journey to heal his own severe childhood trauma and offers profound insights into the evolution of his innovative healing method.

For more info and/or to order this book, click here. Also available as an Audiobook and a Kindle edition.

About the Author

Peter A. Levine, Ph.D., is the renowned developer of Somatic Experiencing. He holds a doctorate in medical and biological physics from the University of California at Berkeley and a doctorate in psychology from International University. The recipient of four lifetime achievement awards, he is the author of several books, including Waking the Tiger, which has now been printed in 33 countries and has sold over a million copies.

Peter A. Levine, Ph.D., is the renowned developer of Somatic Experiencing. He holds a doctorate in medical and biological physics from the University of California at Berkeley and a doctorate in psychology from International University. The recipient of four lifetime achievement awards, he is the author of several books, including Waking the Tiger, which has now been printed in 33 countries and has sold over a million copies.

Visit the author's website at: SomaticExperiencing.com

More books by this Author.