A new documentary shows how one state is confronting Native American child removal.

When we think of the history of forced cultural assimilation of Native Americans into U.S. culture, we often point to residential schools. From the mid-19th to the early-20th centuries, residential schools removed Native American children from their communities, punished them for speaking their home language and practicing their religion, and attempted to assimilate them as working-class members of society. These residential schools are widely known to have been sites of abuse and trauma. But the story of removal of Native American children did not end with these schools. The new documentary Dawnland documents other more contemporary child removal practices and one state’s effort for justice.

In February 2013, the state of Maine launched the Maine Wabanaki-State Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the first government-mandated TRC in the United States. The commission was charged with establishing a more complete account of Native American foster care placement between 1978 and 2012 and with formulating policy recommendations to empower tribal communities and start to reverse generations of colonial violence.

Native American children are overrepresented in the child welfare system. In Maine, in 1972, Native children were placed in foster care at a rate 25.8 times that of non-Native children. They were often placed in non-Native homes, sometimes without any legal proof that their birth parents were “unfit.” Stories like these across the nation led to the passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act in 1978, which legally declared that it is in the best interest of Native American children to stay within their families or tribes. ICWA recognizes the potential damage that child removal does both to the children and their tribe as a whole: How can a tribe continue to exist if it cannot pass on its language, cultural traditions, and history to the next generation? As gkisedtanamoogk, co-chair of the Maine Wabanaki Child Welfare Truth and Reconciliation Commission, reflected in Dawnland on child-removal practices, “You take away a people’s understanding of who they are, their self-sufficiency, and you replace it with nothing.”

Yet decades after the passage of ICWA, Native American children are still removed from their homes at a disproportionately high rate. Between 2000 and 2013, Native children were removed at 5.1 times the rate of non-Native children in Maine. This is one reason the commission was formed. The commission, along with the advisory group Maine-Wabanaki REACH, or Reconciliation Engagement Advocacy Change Healing, began collecting stories in 2013. For the next two years, they gathered testimony from state child welfare staff, children who were placed in foster care or adopted, and parents in Maine’s four remaining tribes who had their children taken away. Dawnland is both an intimate lens into the personal and communal impacts of child removal practices and an exploration of the conflict that arises when White communities and communities of color jointly confront historical trauma and racism.

These tensions play out in real time in Dawnland. One community event for gathering testimony did not have a high turnout, so members of Maine-Wabanaki REACH asked staff from the commission to leave the room to ensure all participants were comfortable sharing their truths. This did not go over well with the commission staff, the majority of whom were White women. REACH co-director Esther Anne Attean defended the decision, saying that the goal of truth-telling is “not about making White people feel welcome.” She argued that part of being an ally is recognizing when you need to leave the room and allow Native peoples the space to share their stories as a form of healing.

We are left to ponder: Whom is this truth-telling for? Is it to educate White people on colonial violence and how it continues to harm indigenous communities in Maine, or is it for the Native participants to heal and be heard? Can it simultaneously be both, or should one be privileged over another?

Though child removal is a sensitive and at times traumatic subject matter, conducting research and making recommendations is the easy part. Sustained healing and an assertive confrontation of colonial and White supremacist violence are much harder. But as the commission’s executive director, Charlotte Bacon, reflected in the report, “None of us is exempt from that responsibility.” We have a collective responsibility to address the ongoing violence of colonialism, and the impacts of child removal on tribal communities and tribal survival.

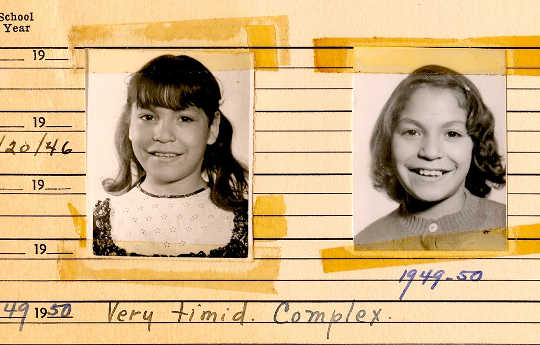

An elementary report card for Georgina Sappier (Passamaquoddy) from Mars Hill elementary in Maine for the years 1947–53. Photo by Ben Pender-Cudlip/Upstander Project.

As the testimony of children removed from their homes makes clear in the film, changing policy alone cannot end the impacts of colonial violence. The commission focused specifically on Native American children in foster care from 1978 to 2012—after the passage of ICWA. Whether intentional or not, racism from foster parents and racism from child welfare staff continues to traumatize Native families.

“My foster mother told me that I was at her house because nobody on the reservation wanted me. ... And that she would save me from being Penobscot,” Dawn Neptune Adams said in the film. She also said she had her mouth washed out with soap when she spoke her Native language.

Like Adams’ foster mother, not everyone sees distancing Native children from their tribal cultures as violent. As with residential schools, some view it as benevolent. Jane Sheehan, a retired child welfare worker who worked in the system for decades, is shown in the film saying that “two sneakers for the feet is sometimes more important than learning an Indian dance.” Intentionally and aggressively confronting racism—particularly unintentional racism coming from ill-informed rather than overtly hateful viewpoints—must be addressed in any truth and reconciliation effort.

Tracy Rector, a producer for the film, is hopeful that Dawnland can help with this process. “In the majority of the screenings to date, the audiences have been primarily non-Native and more specifically White,” she told me. “The vast majority of these audience members often comment that they were not aware of the policies involved in colonization, the boarding schools, or forced adoption and foster care. I see and hear in these discussions that we are building allies.”

Dawnland makes clear that any effort to empower tribal sovereignty and right historical wrongs—what some may call reconciliation—must center indigenous leadership and indigenous healing. While it remains to be seen how Maine and its tribal communities will continue to work toward justice for those most affected by violent child welfare practices, truth-telling is a vital and historic first step. And non-Natives must be willing to listen deeply. As activist Harsha Walia asserted: “Non-Natives must be able to position ourselves as active and integral participants in a decolonization movement for political liberation, social transformation, renewed cultural kinships, and the development of an economic system that serves, rather than threatens, our collective life on this planet. Decolonization is as much a process as a goal.”

{youtube}S9HToApMbkM{/youtube}

This article originally appeared on YES! Magazine

About The Author

Abaki Beck wrote this article for The Good Money Issue, the Winter 2019 issue of YES! Magazine. Abaki is a free-lance writer and researcher passionate about Indigenous community resiliency, public health and racial justice. She is a member of the Blackfeet Nation of Montana and Red River Metis. You can find more of her writing on her website.

Related Books

at InnerSelf Market and Amazon