Image by Gerd Altmann

First, you know, a new theory is attacked as absurd; then, it is admitted to be true, but obvious and insignificant; finally, it is seen to be so important that its adversaries claim that they themselves discovered it. ~ WILLIAM JAMES

How could I have missed the holes in our current scientific worldview? I am just as guilty as anyone. I began this journey not expecting to find scientific evidence for my experiences, because the mainstream scientific materialist narrative suggests that evidence doesn’t exist for unexplained phenomena, and to believe in these phenomena means you are either batty or stupid. Instead, I was searching for personal justification in being at least a little open to spiritual or metaphysical beliefs by speaking with other like-minded people. While I did find that (yay!), I also stumbled across a huge problem in scientific materialism: How could we hope to have a theory of everything when we so narrowly define what kind of evidence from which fields of knowledge can be included?

To borrow Richard Tarnas’s own language, he examines “the great philosophical, religious, and scientific ideas and movements that, over the centuries, gradually brought forth the world and world view we inhabit and strive within today.” This is a worldview driven by the principles of the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment that separated man from nature and emphasized reason above other human faculties. To refer to this worldview going forward, I use “society” for shorthand.

The greatest unearthed treasure on my adventure was discovering that I have more to offer than purely my intelligence, logic, and capability to produce work, even though society suggests these are the most valuable traits I can offer. But, in truth, compassion, kindness, and providing comfort for others are just as worthwhile.

Being a woman in science is already difficult. There are persistent worries of being taken seriously by male colleagues, of how to dress, of how much makeup to wear, of how to speak, and more. Adding spiritual belief in the impossible to that list? Forget it.

But, ultimately, I got so tired of conforming to a fictional ideal that I prioritized being my authentic self. Who is the authentic me? Ah, well that is the point of the journey of life, the self-realization.

Academics, Spirituality, and Unexplained Phenomena

The prevailing attitude in intellectual circles is that no serious person believes, or is even interested, in unexplained or spiritual phenomena. That’s simply not true. Many prominent scientists, physicians, philosophers, and writers throughout history have been interested in bridging spirituality and science, which has sometimes included studying unexplained phenomena.

For example, William James was a member of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR)—a nonprofit started out of Cambridge University that still exists today and performs scientific investigation of extraordinary and unexplained phenomena. Other members included: Nobel laureate and physiologist Charles Richet, Nobel laureate and physicist Sir J. J. Thomson, and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

The legendary psychologist Carl Jung and physicist Wolfgang Pauli had an entire dialogue around the relationship between mind and matter, synchronicity, and spirit, and it was partly to find an explanation for the Pauli effect, a phenomenon where mind-over-matter effects manifested routinely around Pauli.

Nobel laureate in physics Brian Josephson, who was interested in spiritual higher states of consciousness and psi phenomenon, such as telepathy and psychokinesis, called the scientific community’s dismissal of anything mystical or New Agey as “pathological disbelief.”

Marie Curie, the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, attended séances and studied the physics of paranormal phenomena. Francis Bacon performed divination, Galileo Galilei read horoscopes, Isaac Newton studied alchemy, and Albert Einstein wrote the preface to Upton Sinclair’s book on telepathy, Mental Radio (1930).

Scientists Are Not All Atheists

It’s not just prominent historical scientists, either. A 2009 Pew Research survey (Rosentiel 2009) of scientists who were members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science found that just over half of scientists (51%) believed in some kind of higher power (33% believed in “God,” 18% believed in a universal spirit or higher power). Forty-one percent did not believe in any kind of higher power. That’s almost a 50/50 split! I was blown away.

The breakdown of believing scientists varies greatly from the American general population. A majority of Americans (95%) believe in God or some higher power or spiritual force (Pew Research Center 2009a), 24% believe in reincarnation (Pew Research Center 2009b), 46% believe in the existence of other supernatural beings (Ballard 2019), and 76% report having at least one paranormal belief (ESP being the most common at 41%) (Moore 2006).

Do Scientists Believe in the Paranormal?

Although a 1991 National Academy of Sciences survey of its members revealed that only 4% believed in ESP (McConnell and Clarke 1991), 10% believed it should be investigated. However, another study that anonymously surveyed 175 scientists and engineers found that 93.2% had at least one “exceptional human experience” (e.g. felt another person’s emotions, had known something to be true that they would have no way of knowing, received important information through dreams, or seen colors or energy fields around people, places, or things) (Wahbeh et al. 2018).

What an interesting discrepancy that under one set of circumstances, scientists deny believing in ESP, yet under another, they admit to having experiences of it. There could be many reasons for this, such as scientists being uncomfortable reporting their interest in ESP to a prestigious scientific institution and less uncomfortable doing so to a small, anonymous study. Or, it could be because of the differences in wording used in the surveys, such as using “exceptional human experience” instead of “ESP,” a much more stigmatized word in the intellectual community.

If the latter is true, that would be an excellent example of the weight language carries in understanding and expressing our experiences. Very recently, over one hundred notable scientists have called for a post-materialist science where such topics are openly investigated, rather than quietly brushed under the rug (“The Manifesto for a Post-Materialist Science: Campaign for Open Science”).

Dean Radin, Ph.D., chief scientist at the Institute of Noetic Sciences, is trained in electrical engineering, physics and psychology, and performs psi research. Based on his interactions with scientists at scientific meetings, such as those held at the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, in conjunction with the inquiries he receives, he states that his “impression is that the majority of scientists and scholars are personally interested in psi, but they’ve learned to keep their interests quiet. The same is true for many government, military, and business leaders. . . . The taboo is much stronger in the Western world (e.g. United States, Europe, Australia) than it is in Asia and South America” (Radin, 2018).

It’s Not Just Me and You!

Through the dialogues I had with some of my neuroscience colleagues, I realized that they were much more open to non-mainstream scientific research topics than I had thought they would be. I even had a colleague who recounted to me how his brother, when he was under three years old, had shared memories that he could not have known from their grandmother’s life in a country she had previously lived in before getting married. Another colleague, who had at one point been interested in psi research, had even bought dowsing rods to test them out. I had yet another colleague who, when I went to describe the research that I had been reading about telepathy, clairvoyance, and precognition, was already familiar with it and had read much of it himself.

I’m not claiming that they’re all believers, but rather highlighting the fact that we were all interested in unconventional topics and didn’t know that about each other. What fun conversations had we missed out on?!—I blame scientific materialism.

Because spiritual, mystical, or unexplained topics are taboo in mainstream science, it felt like my experiences were unique to me and I was alone in being curious about them. That’s why I am making the point here that many, many academics are interested in spiritual and unexplained phenomena, or typical human experiences, as I now think of them.

We’re actually not alone at all. If more academics, and especially scientists, could shake off the invisible, but restrictive, shackles of culture and publicly admit their interest in unexplained mysteries, maybe we could explain the unexplainable.

What Else Are We Missing?

By excluding certain topics from scientific investigation, could we be missing other important findings in science?

If it’s true that consciousness is fundamental and our minds interact with matter, what are the implications for the scientific method, which assumes an independent, objective observer/experimenter? What are we missing by ignoring this connection?

What if when things come together, like an experimenter and a subject, they form a whole or a system, and are no longer independent (think of how schools of fish swim or flocks of birds fly together)? And what about statistics? We colloquially and scientifically throw around the words “by chance.” What force or law governs “chance”? Think of the bell curve, how it shows the majority of individuals in a population will fall in the middle of the curve for some trait (let’s say altruism) and tapers off on the lower and higher ends.

When we perform an experiment and recruit participants, we hope to find that in our study altruism among our participants falls along a bell curve indicating that we have a distribution that is representative of the general population. In fact, our statistical analysis can depend on it.

But what force governs which subjects show up for your study enabling you to achieve that bell curve? Is there ever such a thing as something being truly due to chance? Thinking this way brings up a lot of questions around what we hold to be true in science.

Increasingly, scientific materialism proposes that our beliefs and behaviors should be firmly planted in rock solid evidence and empirical data. Besides the glaring problem that humans clearly do not operate in this way, as evidenced by the entire history of humankind, during which many ill-advised and seemingly irrational leadership decisions have been made, there is another problem.

The problem with that notion is the inherent assumption that humans have the technological or methodological means to measure and collect evidence and data on everything in the Universe, meaning that we have already discovered all properties of the world. If that assumption is not true, but we behave as if it were true, we will be potentially missing out on having a complete understanding of the Universe. Why would we do that?

Over-emphasis on “Evidence-based” Criteria

Western society’s recent over-emphasis on “evidence-based” and “data-driven” criteria has me concerned, because evidence and data cost money. Let me explain. Clearly it is beneficial to have evidence proving something works as intended, for example a medical device. The problem arises when we erroneously conclude that something doesn’t work or doesn’t exist simply because there is no available evidence to support it.

The phrase, “There is no evidence to support that,” is sometimes used by scientists and journalists in a disingenuous way. When the public hears that phrase, they assume the thing has been investigated and no evidence was found to support it, when in fact, what is usually meant is that the thing has not been investigated. So why not just say that?

It is misleading and is constantly used to knock down anything not accepted by scientific materialism. Moreover, usually, the lack of investigation is not typically due to lack of interest—it is usually because of lack of funding.

The majority of science funding in the United States comes from the federal government. The research agendas of most research scientists at academic institutions across the country are determined by what the scientist believes will get funding.

Research funding for other topics can come from private foundations, but those funding streams are driven by the personal interests of the wealthy individuals who established the foundations. So, please think of this when you hear someone throwing around the word “evidence-based.” It would be really nice to have enough money for researchers to investigate anything they wanted and all the interesting questions in the Universe, but in reality, research agendas, and thus evidence and data, are dictated by money, the interests of the government, and wealthy individuals.

Taking This One Step Further

What if there are things that can’t be measured or explained by the scientific method itself? By deeming the scientific method the only important way to measure and understand the world around us, we are inherently saying that if something exists in the Universe that can’t be measured by this method, then it is not important or worth knowing.

There is a contradiction between believing that we only know for certain what we can measure and observe and the fact that we are using our brains to measure and observe. We know that both physics and quantum physics are true, but we can’t reconcile them, and yet we persist in declaring that the scientific method is the method.

The limitation of the scientific method is something I encountered on my journey that helped me accept personal proof in addition to scientific proof, and it is also the reason consciousness itself is so hard to study.

There are just some things about the human experience that are hard to quantify and that aren’t replicable. Science can’t measure those experiences, and they are usually delegated to the humanities—but then there is no communication between the humanities and science when developing theories about the Universe.

We don’t experience life in two dimensions, with separate scientific and humanities experiences; it’s just one life experience. We need to include both the sciences and the humanities in constructing theories of this stunning, horrid, blissful, cruel thing we call life.

A Meaningful and Mystical Universe

Understanding that consciousness could be the foundation of the Universe reframed my thinking in such a way that unexplained phenomena did not seem extraordinary any longer. It all seemed really simple, actually, and not a big deal.

When I moved outside the scientific literature into the suggested reading from “the people who know,” I learned that the Greeks used the word Cosmos to describe the Universe as an orderly system. This is an ancient idea found in most cultures across the world since the beginning of the emergence of humanity.

At the confluence of science and spirituality, a new worldview emerged for me: The Universe has meaning and there exists a spiritual and mystical dimension to life. Believing that we are interwoven with the Cosmos and that there is no true distinction between mind and matter, outside and inside, or you and me has actually been the foundation of reality longer than it hasn’t.

Copyright 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Printed with permission of Park Street Press,

an imprint of Inner Traditions Intl.

Article Source:

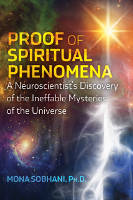

BOOK: Proof of Spiritual Phenomena

Proof of Spiritual Phenomena: A Neuroscientist's Discovery of the Ineffable Mysteries of the Universe

by Mona Sobhani

Neuroscientist Mona Sobhani, Ph.D., details her transformation from diehard materialist to open-minded spiritual seeker and shares the extensive research she discovered on past lives, karma, and the complex interactions of mind and matter. Providing a deep dive into the literature of psychology, quantum physics, neuroscience, philosophy, and esoteric texts, she also explores the relationship between psi phenomena, the transcendence of space and time, and spirituality.

Neuroscientist Mona Sobhani, Ph.D., details her transformation from diehard materialist to open-minded spiritual seeker and shares the extensive research she discovered on past lives, karma, and the complex interactions of mind and matter. Providing a deep dive into the literature of psychology, quantum physics, neuroscience, philosophy, and esoteric texts, she also explores the relationship between psi phenomena, the transcendence of space and time, and spirituality.

Culminating with the author’s serious reckoning with one of the foundational principles of neuroscience--scientific materialism-- this illuminating book shows that the mysteries of human experience go far beyond what the present scientific paradigm can comprehend and leaves open the possibility of a participatory, meaningful Universe.

For more info and/or to order this book, click here. Also available as an Audiobook and as a Kindle edition.

About the Author

Mona Sobhani, Ph.D., is a cognitive neuroscientist. A former research scientist, she holds a doctorate in neuroscience from the University of Southern California and completed a post-doctoral fellowship at Vanderbilt University with the MacArthur Foundation Law and Neuroscience Project. She was also a scholar with the Saks Institute for Mental Health Law, Policy, and Ethics.

Mona Sobhani, Ph.D., is a cognitive neuroscientist. A former research scientist, she holds a doctorate in neuroscience from the University of Southern California and completed a post-doctoral fellowship at Vanderbilt University with the MacArthur Foundation Law and Neuroscience Project. She was also a scholar with the Saks Institute for Mental Health Law, Policy, and Ethics.

Mona's work has been featured in the New York Times, VOX, and other media outlets.

Visit her website at MonaSobhaniPhD.com/