Image by Lorri Lang

All sibling relationships have their ups and downs, good times and bad. But in a family with abuse, addiction, and mental illness, the relationships are warped by a range of dysfunctional dynamics, including the roles each child is forced to play. Even in our younger years, our lives were shaped by the roles we were forced to play in our family: the hero and the scapegoat.

Despite the harmful dynamics in our home, we both have memories of fun times with each other, and with other kids.

Ronni: When I think back over our childhood, I remember getting along pretty well much of the time. Up until I was about 12, the three of us would do lots of things together. We had good times together, the three of us, when we were very little. We were very imaginative.

Jennie: We all loved the world of make-believe. We would play outside with the neighborhood kids, and we’d recreate TV shows, like “Treasure Island.” We would make up all kinds of stories and act them out. We played well with the neighborhood kids, too.

Ronni: We did, generally, have a good time all together, but it wasn’t totally idyllic. I remember that if you couldn’t keep up with what we were doing, our brother and I would call you “a baby.” When I think back on our childhood now, I try to sort out how much of it was kids being competitive and rivals, and how much of it was abusive. I know we made fun of you for being smaller, younger, or not being able to keep up with everything we were doing. When we played Keep Away, or Hide and Seek, or Kick the Can—those kinds of things—it was harder for you to keep up with your shorter, smaller legs. So, we did pick on you for that.

Because we had to do chores together, from an early age, we would sometimes try to find the fun in them as well—for example, racing to see who could finish first, or making some other game out of the task.

Imitating the Abusive Behavior of Our Parents

Despite the good times we remember, we also recall a great deal of abusive behavior amongst the three of us—beyond the name-calling. Our parents hit us throughout our childhood to try to get us to do what they wanted us to do, or to have a target for their rage. The three of us imitated that behavior in our interactions with each other. There were many times, in the course of an argument, where we would push, hit, or slap each other.

Ronni: Mom would get mad at us for hitting each other. She would say, “People are for loving, not for hitting,” and then she would beat us to emphasize that point. It was ridiculous because they were modeling that abusive behavior for us. They were reinforcing the idea that hitting someone to try to get them to do what you want is an acceptable way to behave. Or that it’s OK to hit someone when you’re mad. So, we imitated that behavior.

The Young Hero

In addition to imitating the abusive behavior we experienced from our parents, we settled into our assigned roles at very early ages. Neither of us remember a time when we weren’t seen, or treated, as the hero or the scapegoat. The roles shaped how we behaved, how we saw ourselves, and how we treated each other. Jennie has always seen Ronni as a hero. For as long as she can remember, Jennie has looked up to Ronni. She was beautiful, capable, and everything Jennie wanted to be.

As the hero and big sister, Ronni gained Jennie’s admiration from an early age. She didn’t want to compete with Ronni, or be her, Jennie just wanted to be with her, like her.

Ronni was also conditioned to be in charge, and to manage whatever came along. Whatever trouble we three kids got into along the way, the responsibility always fell more heavily on Ronni.

Two Against One: Creating the Scapegoat

While the parents in a dysfunctional family push their children into their respective roles, the children typically assist in keeping each other in their place. They are taking their cues from the parents; they don’t know any better. In our household, Ronni and our brother were often allied against Jennie, cementing her place as the scapegoat.

Ronni: It was two against one. We would both pick on you. We called you names and excluded you. And we began to create this narrative that you were a problem. Our brother and I rarely fought. You and our brother did not get along, mostly because he antagonized you at every opportunity. And you and I fought fairly often, so our brother and I decided that you were the problem—after all, you were the common denominator. And as I got older, I remember thinking that I never wanted to have three children, because I didn’t want to see that two-against-one dynamic. It seemed inevitable.

With the understanding of our family that I have now, I realize that it doesn’t have to be that way if parents intervene appropriately and are not modeling abusive behavior for their children. But one of the lessons I drew from our childhood was that three is a bad number.

Jennie: That’s interesting. For me, that connects to the memories of Dad repeatedly saying that what ruined his life was getting married too young and having too many kids. I was the third of three so, mathematically, I wasn’t supposed to be there. I destroyed his life and his dreams. It wasn’t about the choices he made. He put his misery squarely on our shoulders. So, I think you and our brother were internalizing these messages from our parents.

Our brother could be very cruel to Jennie. Often, he simply ignored her. Other times, he seemed to look for ways to antagonize her, like catching spiders and throwing them in her face because he knew she was afraid of them. But Ronni could be mean, too. And often, she and our brother were in it together.

Ronni: As we got older, we all became very explicit about naming you as the “identified mess” in the family. We used to say, “Everything would be all right if Jennie would just get her shit together.” Sometime in your teen years, for your 14th or 15th birthday, our brother and I actually discussed buying a bucket and painting “Jennie’s shit” on it, and giving it to you as a “gift.” We never did it, but we started saying we were going to do it, in front of you, and then the whole family would laugh. It was a total team effort—our parents, our brother, and me—to hang all the family dysfunction around your neck.

Jennie: In hindsight, I was fighting a war on every front. I was bullied at school. I was bullied at home. My feelings didn’t matter. I didn’t matter. And I needed to do what I was told. So, I was conditioned to be a people pleaser because fighting didn’t work. I wasn’t strong enough. I wasn’t big enough. I wasn’t capable.

Ronni: There was no question of fighting back with Mom and Dad. And if you tried to fight back, with our brother and me united against you, you weren’t going to win either.

Jennie: And that created all kinds of boundary issues for me, to this day, even with my own children. You and I have talked about this. I love my children and they love me, but I let them get away with more sass than I probably should. Because I think, “Well, they’re having a tough day” or “I know they’re struggling right now, so I’m going to let that slide,” but it really is a boundary issue. It’s something that I’m still working on in my life—trying to come back to “I do matter. My feelings matter, how I’m talked to and how I’m treated matters.” But it’s been a long road.

Ronni: I’m sorry. I’m so sorry. I still feel terrible about the way I treated you as a kid. I know that you forgave me a long time ago, but it’s really hard to forgive myself, especially knowing how much pain and damage I caused.

Jennie: You were a kid. You were a child, too. It breaks my heart when I think of you and our brother—the roles our parents created for us out of their own mental illness and their abusiveness. None of us had a choice in that.

And the result is, I was conditioned to be a doormat and a people pleaser—to placate in order to survive. But I also wanted connection. I wanted to feel camaraderie with you and our brother. That’s why it was so easy to make up. We made up very quickly because all I ever wanted was to be friends. You two used to tease me, chide me, saying: “Jennie, life isn’t the Brady Bunch.” Well, why can’t it be? Because that’s all I ever wanted. I wanted to be able to love you guys. That’s why I think I focus so much on the good memories. I don’t like to think about the painful ones. Honestly, I’ve blocked a lot of them out.

Ronni: The same is true for me. I can remember some mean things I did to you, but I don’t have a lot of specific memories. Probably because I don’t want to think of myself as the kind of person who would do those terrible things. So, you’ve blocked your memories out because you don’t want to relive them, and I probably blocked some of mine out because I don’t want to think that they are a reflection of who I really am, at my core.

That represents a real challenge for someone trying to break through their denial, and piece together memories of their childhood. If you’re trying to work with a sibling, you might have a hard time coming to a common history, or sense of what happened.

It gives us no pleasure to revisit the ugly and abusive dynamics in our relationship as children. But it is imperative that siblings realize that there may be much to work through, and forgive, as they chart their own path of recovery. Some things may be seen as unforgivable by the victim. In this case, the perpetrator’s only course of action is to continue to express remorse and demonstrate a clear desire to improve the relationship by making loving, supportive choices moving forward. In that way, it may be possible to rebuild trust.

We also hope that, by telling the whole truth about our sibling interactions, we can shine a bright light on the serious problem of sibling abuse. It is the most common, least understood, and most damaging form of family violence.

A wide range of abusive behavior is often normalized as “sibling rivalry”—even in families with healthier dynamics than ours. But, as Jennie’s experience shows, this kind of behavior cannot simply be shrugged off as “kids being kids.” The devastating impact of sibling abuse on one’s self-image and sense of wellbeing can take a lifetime to repair.

Repairing the Gulf Between Us

As we moved into young adulthood, we began to recognize that our relationship was not what we wanted it to be, but it took time to repair it. We had prolonged periods of time where we did not communicate regularly, but our concern for each other, and desire for a better relationship, are obvious in the ways we reached out to each other, and offered assistance, at critical points in each other’s lives.

Ronni: When I was at college, we only saw each other at the summer break, or if I came home briefly between semesters, because my school was so far away. The whole time I was in college, I would call home once a week, but I didn’t talk to you. I talked to Mom and Dad. You and I wrote some letters back and forth, but not many.

Jennie: And you worked hard in school. You had grants, loans, scholarships, work study. Mom and Dad sent you a little spending money every two weeks when Mom got paid. But your last semester there was some hiccup with your grant money. You were short about $600. You called home to say that you weren’t going to be able to go back for your last semester. Our uncle had just sold my horse several months earlier, so I had money sitting in a savings account. Mom and Dad didn’t have any money to send you. But I had the money from my horse, so I sent it to you.

I was so excited to be able to do something for you because you didn’t need me—you didn’t need anybody. That’s what I felt at the time. “Ronni doesn’t need anybody. She’s cool. She’s on her own. She’s making it happen.” I was tickled that I had the money, so I wrote you a letter and sent you a check. I told you it was a gift—that I did not want you to pay it back. I was so happy to be able to do it.

About that time, Jennie was in an abusive dating relationship, and it was Ronni who reached out to her; she tried to build Jennie up, telling her that she deserved better, and figured out a way to help Jennie move away temporarily, so that the relationship could cool, and Jennie would be free to start over.

Building Our Families

The families we are born into set the stage and tone for our lives as children. We then grow up to create our own families in the image of what we know best, including those of us who experienced abuse, addiction, mental illness, and other dysfunction in our homes. It happens unconsciously—sometimes in spite of our desire to do things differently—and creates a long chain of intergenerational trauma.

It takes a sustained and concerted effort to break that cycle. Without that commitment, it is very easy to end up with a partner that is abusive, and to hear your parents’ words come out of your mouth.

Unraveling the dynamics from our childhood, and building a loving bond between us, has taken years of effort. We both feel extremely fortunate that we were able to find loving, caring partners at very early ages, and that we had each other’s constant support as we built our own families. This has allowed us to heal the wounds of the past, and to rewrite our parenting script so that our children could have happier childhoods than our own. And it is the proudest accomplishment of our lives.

Copyright 2022. All Rights Reserved.

Printed with permission of the authors.

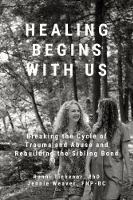

Article Source:

BOOK: Healing Begins with Us

Healing Begins with Us: Breaking the Cycle of Trauma and Abuse and Rebuilding the Sibling Bond

by Ronni Tichenor, PhD, and Jennie Weaver, FNP-BC

Healing Begins With Us is the story of two sisters who weren’t supposed to be friends. Ronni and Jennie grew up in a home with addiction, mental illness, and abuse issues that generated unhealthy dynamics and often pitted them against each other.

Healing Begins With Us is the story of two sisters who weren’t supposed to be friends. Ronni and Jennie grew up in a home with addiction, mental illness, and abuse issues that generated unhealthy dynamics and often pitted them against each other.

In this book, they tell the raw truth about their childhood experiences, including the abuse that occurred between them. As they moved toward adulthood, they managed to come together and chart a path that allowed them to heal their relationship, and break the cycle of intergenerational trauma and abuse in creating their own families. Using their personal and professional experience, they offer advice to help others who are looking to heal from their own painful upbringings, or heal their sibling relationships.

For more info and/or to order this book, click here. Also available as an Audiobook and as a Kindle edition.

About the Authors

Ronni Tichenor has a PhD in sociology, specializing in family studies, from the University of Michigan. Jennie Weaver received her degree from the Vanderbilt School of Nursing and is a board-certified family nurse practitioner with over 25 years of experience in family practice and mental health.

Ronni Tichenor has a PhD in sociology, specializing in family studies, from the University of Michigan. Jennie Weaver received her degree from the Vanderbilt School of Nursing and is a board-certified family nurse practitioner with over 25 years of experience in family practice and mental health.

Their new book, Healing Begins with Us: Breaking the Cycle of Trauma and Abuse and Rebuilding the Sibling Bond (Heart Wisdom LLC, April 5, 2022), shares their inspiring and hopeful story of healing from their painful upbringing.

Learn more at heartandsoulsisters.net